Rush found me in high school, through an older friend who knew of such things. We were band nerds together, but he was also into coding, RPGs, elaborate pranks, scaling walls and going on abandoned mall raids. He drove us around in his Jeep, had an attic where we could bash out rock covers, and actually owned a Chapman Stick. Jonathan was super smart, a little awkward and shy, but genuinely kind, driven, altruistic– the kind of person who was never going to be “popular”, but we fellow misfits knew was the real deal.

I loved Rush instantly. Circa 1989, I had only recently discovered Led Zeppelin, Yes and The Police, but Rush simply did stuff no other band could. The sheer power of their riffs and beats blew me away. They made epic songs that were somehow both as fun and as serious as Star Wars (it being my most unimpeachable benchmark of quality). They had tons of small details to obsess over. I remember a specific moment in “Cygnus X-1” (1977) where everything except guitar drops out. Guitarist Alex Lifeson lays down these weird rhythm patterns featuring minor seconds as passing tones, like something Stravinsky would have done with muted trumpets. Nobody in my world could compete.

As I heard it then, and still do, the single coolest thing about the band was drummer Neil Peart. Granted, it wasn’t hard to be the coolest thing about Rush: beyond the fact they didn’t play anything like “pop” music, their vocalist had a singing timbre with, shall we say, niche appeal. Even as someone coming to them from other hard rock bands, I had a hard time with the banshee squeal of bassist/singer Geddy Lee, but since their songs had so many other cool parts (including Lee’s own bass playing), I learned to accept it.

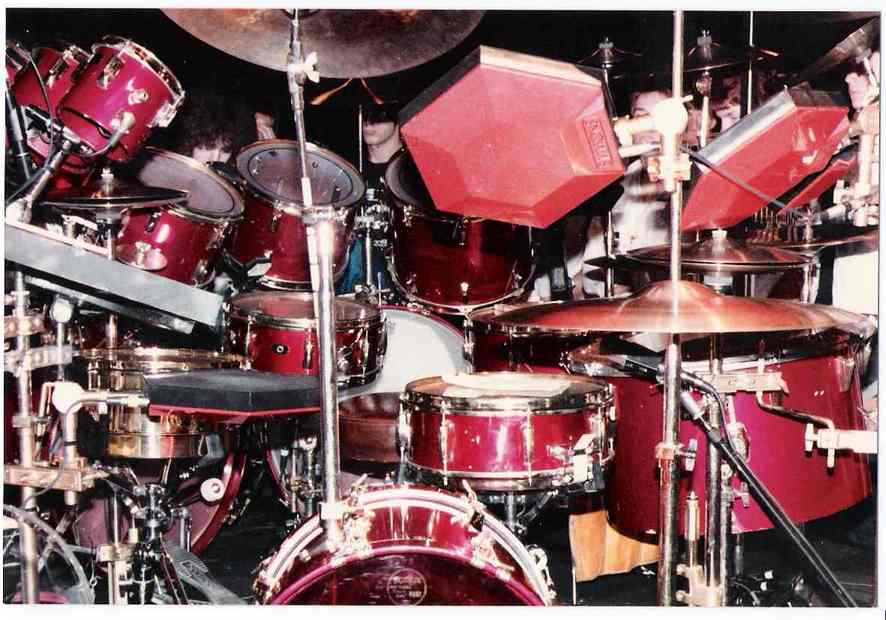

I had no such qualms with Peart’s playing. It jumped out of the speakers — hell, out of the songs themselves – straight into my budding, adolescent power zone. He played with more dexterity and flash than any drummer I’d ever heard, and seemed to bash the shit out of his drums. And he didn’t just play stock rock beats, his stuff was FAT. Seriously, can any rock drumming ever compete with “Tom Sawyer“? Not just the verse pattern (which by itself is tough enough to act as theme song for WWE wrestlers), but the fills, the production, the pacing. He didn’t play to impress you, but used technique to turn his beats (and those songs) into weapons-grade aural attacks.

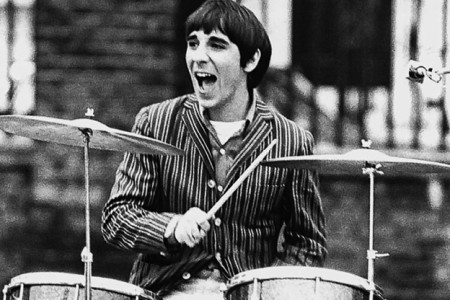

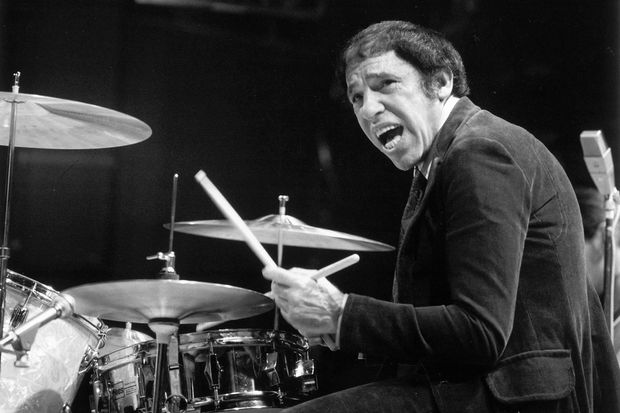

Granted, most of Peart’s figures had ostensibly been covered by the other big hard rock bands of the time, from Zep to Deep Purple, and going back to Hendrix, Cream and The Who, but with an unprecedented exactitude and thundering impact. With 30 years of hindsight, I can recognize some of the constituent parts of Peart’s playing. He’d come up at a great time to be a rock drummer, since cats like Keith Moon, Mitch Mitchell, Ginger Baker, Michael Shrieve, Bill Bruford, Billy Cobham and John Bonham were re-writing the trap set handbook on a nightly basis.

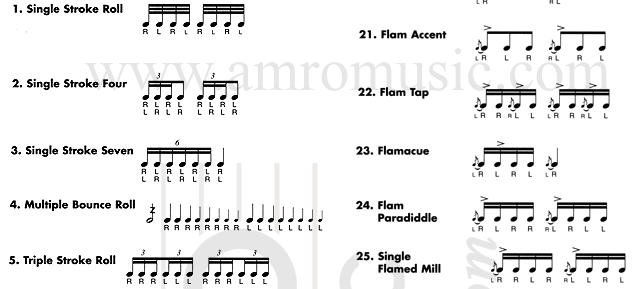

Prior to the late-60s, drum set expertise was judged almost exclusively from jazz players: Max Roach, Art Blakey, Gene Krupa, Louis Bellson and of course one of Peart’s chief inspirations, Buddy Rich. Peart studied those guys (reportedly being first inspired to play drums after watching the ’59 biopic The Gene Krupa Story), but thinking he’d never be able to reach their level of expertise, stuck to playing rock. But technical he was, most obviously in his lifelong application and mastery of the snare rudiments that so many young percussion students must learn. Single-strokes, double-strokes, paradiddles, double-paradiddles, flamacues and the rest. Like the great drummers he admired, he used rudiments as tools for developing what became a historically unique, varied style.

Personally, I hear Moon in Peart more than the others, in the way they both laid waste to their kits with near inhuman energy, speed, volume and endurance. It was as if their internal clocks ran faster and louder than mine could, and I’d only ever be able to understand what happened in retrospect. Moon’s animal intensity couldn’t ever truly be imitated, so in a perfectly modern adaptation, Peart quantized and compressed it, making each stroke even, clear and in perfect time. If Moon was a blind fury of energy, Peart was the refinement, a master of preparation and perfect execution.

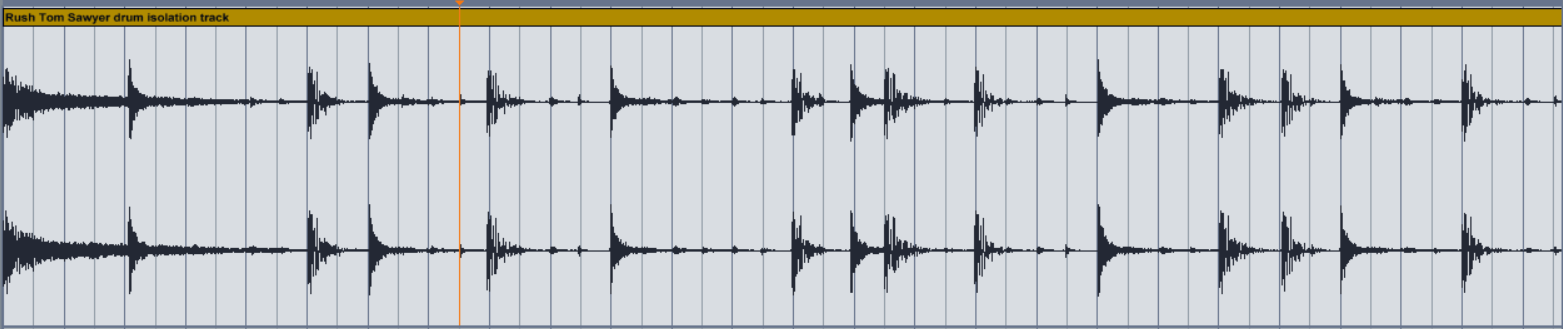

But what does that even mean? Was Peart really so different from other rock drummers? I think so, and I’ll start with his time. If you take a song like “Tom Sawyer”, and just look at the beat itself — the pattern of notes arranged for kick, snare, hat and cymbals – it’s not much different than what any classic rock drummer might do over 174 bpm (or what it really sounds like to me, 87). Bonham or Moon, for example, could have jammed a similar beat up and down the heavens.

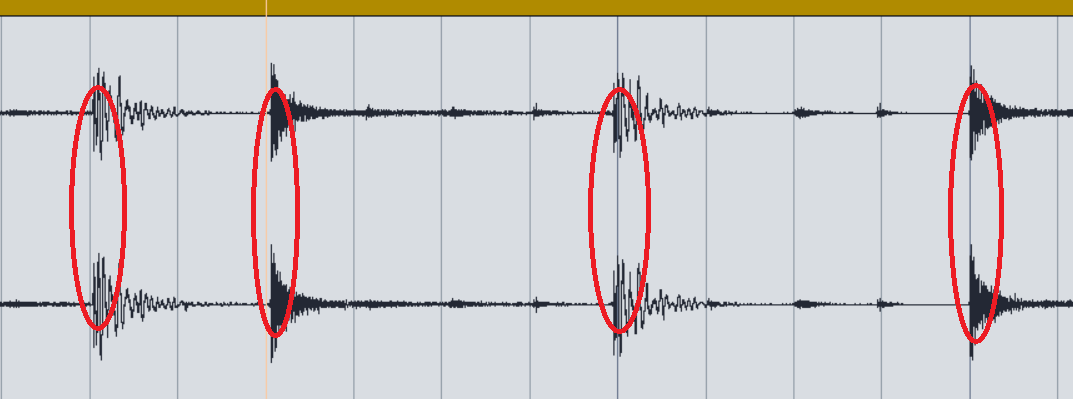

They couldn’t have played it like Peart, though. Take a look at the audio file from the original 1981 recording of “Tom Sawyer”:

Now, Peart’s admitted that he recorded with a click track, which is hardly unusual in the pop/rock world. However, the click usually plays only the quarter notes, so it’s up to the drummer to keep it together the rest of the time. Most pros manage okay, but Peart was like a machine. Each of those lines in the graph above represents a 16th-note, and the dark arrows that pass through them represent Peart’s playing. Do you see any of them more than a millimeter off a mark? Me either.

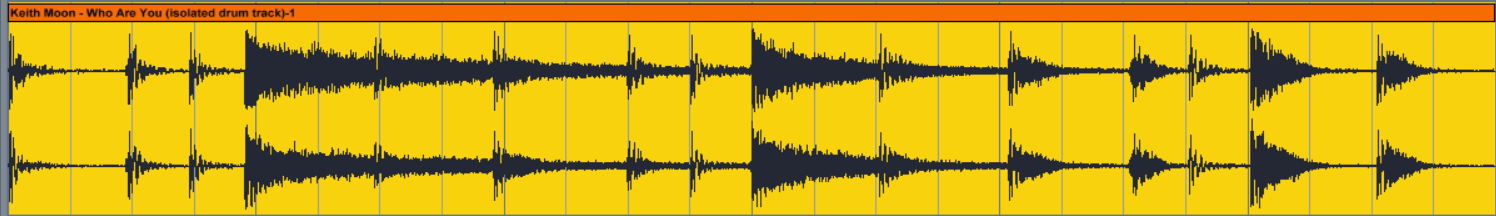

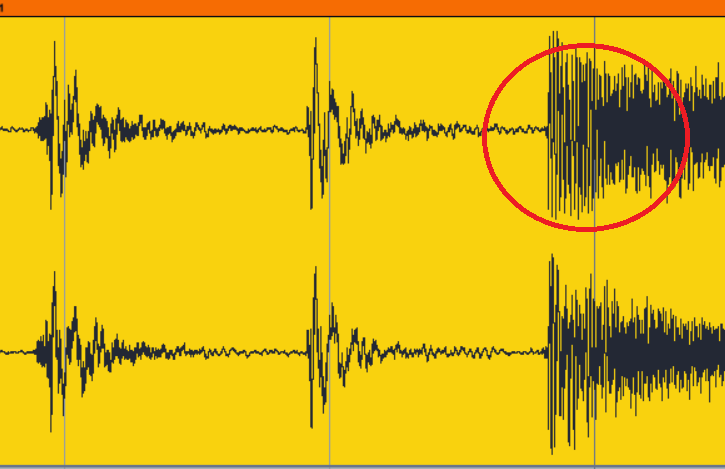

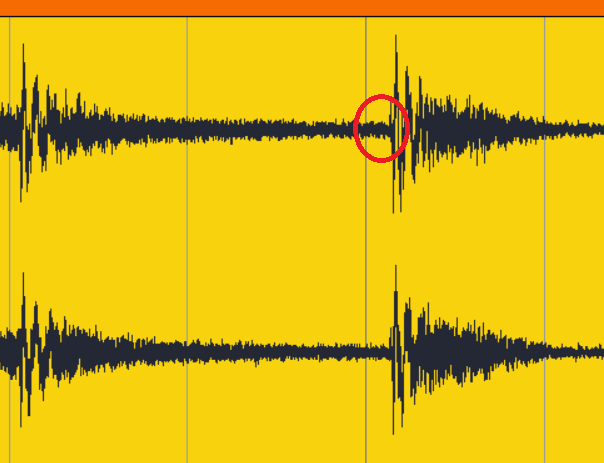

Compare that to a Moon performance in roughly the same style, “Who Are You”. Notice he’s actually ahead of all the beats in the first half of the phrase, and behind the ones in the second half, like a musical rubber-band.

Moon ahead |  Moon behind |

Peart’s time was closer to what a drum machine would do than a human. I’m not saying that made for “good” style in and of itself, as real groove is almost never right on the beat. But, it was unusual (not to mention difficult), and in the context of how technologically powered popular music would become in the 80s and beyond, oddly prescient.

Of course, progressive drummers like Can’s Jaki Leibezeit or Neu!’s Klaus Dinger had already been compared to machines, emphasizing either metronomic precision, mechanical repetition or both. But Peart’s factory-grade perfectionism was applied to decidedly non-minimalist, highly-structured music; night after night, to arena crowds. Rock critics called Rush “dinosaurs”, but they were on far better terms with the digital age than many cared to admit, if they realized it at all.

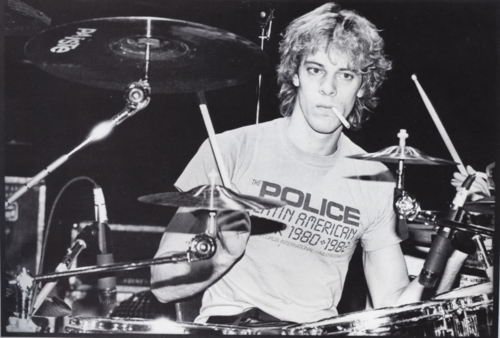

Peart relentlessly sought out new information and styles he could integrate into his playing, augmenting the way he thought about music. In some cases, like his adoration of The Police’s Stewart Copeland, you could hear stylistic changes that seemed directly attributable to newfound inspiration, like the reggae break in “Spirit of Radio”. Other times, as when he changed his technique and grip in the mid-90s (after studying with renown drum pedagogy guru Freddy Gruber), changes were subtle.

Rush’s mid-80s minor renaissance records Signals (1982), Grace Under Pressure (1984) and Power Windows (1985) showed not only a willingness from Peart to simplify and optimize his parts, but to be produced in a way that felt true to its time. Bring on the gated reverb! The refined EQ and electronic drums of the New Romantics! Most importantly, integrate the minimalist, driving patterns of the New Wave! Peart digested the era’s innovations with gusto, and I’d argue that other than Copeland and maybe Phil Collins, his “sound” drove the decade most, in terms of drum production.

By the 90s, Peart’s influence was already deeply woven into rock. Can you imagine extreme metal without him? How about Primus or Dream Theater? Metallica or Mars Volta or Mastodon or Soundgarden or the Foo Fighters? The question of influence in music is tricky, because inspiration never comes from just one place – it’s a combination of experience, facility, location, pretty much any factor you could name. But to think of any modern rock drumming performance without the impact of Peart is to think of something completely different than what we hear today. And probably a lot lamer.

Precedents and drumming styles aside, Rush’s drummer was the heart and soul of his band. He famously wrote most of their lyrics (and we’re hardly talking about typical love/sex/rebellion themes). They were existential. Peart’s songs were about questioning the status quo (“The Trees“), retaining humanity in the face of technology (“Digital Man“), hanging on to the power of music when the biz tells you it’s image that matters (“The Spirit of Radio“), Rand-ian individuality (“Tom Sawyer“), and just getting through life when you’re not cool (“Subdivisions“). They weren’t necessarily unusual subjects, but Peart’s prose — literate, honest, direct, skeptical but optimistic – stood out, even beyond the spirited musical backing. Could it come off as pretentious? Sure, but who cares? Frankly, Peart could have written in a made-up language, and I’d have still loved him.

In person, Peart seemed introspective but enthusiastic, and slightly nerdy. Watching him speak in interviews, I felt his unease at being asked to talk about himself, even as his enthusiasm for music overtook his shyness. His speech, like his drumming, was considered but jubilant. Each word was chosen with care, just as each drum part was designed in accordance to its constituent song’s needs. Peart was an introvert, and escaped into books, and on long motorcycle treks while on tour just to get out of the loop of publicity, soundchecks, shows and tour buses. He didn’t do any drugs, so I imagine that was his recharge.

In the mid-90s, after decades of playing and touring, Peart began to experience the first signs of degraded physical performance. It was then he sought out Gruber, and went back to traditional grip. He described trying to conceive of his kit as part of a great circle, and to re-orient his limbs to operate more gracefully therein, rather than merely “aim at the floor and play right through the drums.” He wanted to loosen up, swing harder, and keep playing for as long as his limbs would let him. He continued to tour and record with Rush for 20 more years.

And now, he’s gone. Fuck. Truthfully, I haven’t listened to Rush much since college, but it still hurts. I told my wife it was kind of like when MCA died, with the passing of someone who represented the best of what I might hope to experience as a musician — but Neil was a lot more important. As much as his drumming inspired me, and countless others, over the past 45+ years, it was his individual spirit and commitment to simply being (and trying to better) himself that inspired most. Peart never fit in. He just loved the drums, and made me love them too.

Thanks Neil, I’ll miss you.

We’ll put.

My sentiments exactly,sir.Mr.Peart had

class.Been playing 48 years.No other drummer has had near as much influence on my style.Thank you much for a great piece.

Farewell to my hero.

You are right, Rush music above and beyond other’s, they were distant from other bands, better lyrics and style. I have seen them 14 times, thought l would see them again, l was wrong. I cried when l heard, never met him but his lyrics changed my life.

Great analysis and explanation. I appreciate your comments and I know Neil would have as well. Thanks for sharing and taking the time and care to write it. I know from personal experience that Neil was a great thinker and in the earlier days had far less to say He let his performance speak for him which worked to his advantage because most people aren’t as interested in what people have to say but with music it has and always will transcend all language barriers… lucky for us..Adam.R

I don’t think the Music World has realized what they have lost since the passing of Neil Peart , not just the most incredible drummer on the face of the Earth , but he was also a Great Husband , a Great father , and a Great friend , to Mr. Lifeson , and Mr. Lee !!!